Nestled in the misty mountains of the southeastern United States, Appalachia is a region rich with a diverse cultural tapestry woven over centuries. Known for its stunning natural beauty, this rugged area is equally celebrated for its deep-rooted traditions in music, food, crafts, and storytelling. These practices, passed down through generations, are not only a reflection of the people of Appalachia but also vital elements of the region’s identity. From the soulful notes of a fiddle to the savory flavors of cornbread, Appalachia’s culture is a living narrative — one of creativity, community, and history.

Appalachian Music: A Soulful Soundtrack

Music is perhaps the most iconic and far-reaching cultural hallmark of Appalachia. Influenced by Irish, Scottish, African, and Native American traditions, Appalachian music has evolved into a distinct genre that includes bluegrass, country, and folk. Its raw, unpolished sound often draws listeners in with its haunting melodies and heartfelt lyrics.

In Appalachia, music is more than entertainment—it is a means of storytelling, a way for the region’s residents to express their struggles, joys, and dreams. The fiddle, banjo, guitar, and mandolin are the instruments that bring this tradition to life. The music is often performed at community gatherings, with local musicians passing down songs from one generation to the next. These songs—tales of love, loss, hardship, and celebration—reflect the history and spirit of the Appalachian people.

One of the most notable figures in Appalachian music is the Carter Family, who helped define country music in the early 20th century. Their songs, such as “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” capture the deep sense of community and spiritual life that permeates Appalachian culture. Today, artists continue to honor this tradition, keeping the music alive and evolving in new and exciting ways.

Appalachian Food: A Taste of Tradition

No exploration of Appalachian culture would be complete without delving into the region’s rich culinary heritage. Rooted in the practical necessity of living in a rural, mountainous area, Appalachian cuisine is a reflection of its people’s resourcefulness and creativity. The region’s food is often hearty and simple, yet it’s filled with a depth of flavor that tells the story of generations.

Staple foods like cornbread, biscuits, beans, and greens are common in Appalachian kitchens. Traditional dishes like fried chicken, country ham, and collard greens are prepared with love and care, often passed down through families as secret recipes. In the fall, Appalachian tables are adorned with fruits of the harvest, such as apples, peaches, and pumpkins, which find their way into pies, jams, and preserves.

One of the most beloved dishes in Appalachian cuisine is “gravy and biscuits”—a comfort food that has nourished generations. The gravy, made from sausage drippings, is often served with biscuits and eggs, epitomizing the region’s spirit of resourcefulness and home-cooked comfort. These dishes, while simple, are infused with meaning and nostalgia, offering a taste of home to anyone who partakes.

Appalachian Crafts: A Celebration of Handiwork and Heritage

Craftsmanship is another pillar of Appalachian culture, with artisans throughout the region continuing to preserve traditional techniques. From quilting and weaving to pottery and wood carving, Appalachian crafts are as diverse as the region itself. These crafts are not just about creating beautiful objects—they are about maintaining a connection to the past and honoring long-held traditions.

Quilting, for example, has a rich history in Appalachia, with intricate patterns and designs often passed down through families. The art of quilting was often a communal activity, with women coming together to share stories while working on a quilt. Each stitch held meaning, and the quilt itself became a symbol of the community’s unity and spirit.

In the mountains, wood carving and basket weaving are also prevalent, with artisans using local materials like oak, hickory, and sweetgrass to create functional and decorative pieces. Pottery is another important craft in Appalachia, with the region’s early settlers using the rich clay deposits found in the area to create functional pottery for everyday use.

These crafts, though simple, carry the weight of history and serve as a tangible reminder of the strength and ingenuity of the Appalachian people.

Appalachian Storytelling: A Tradition of Oral History

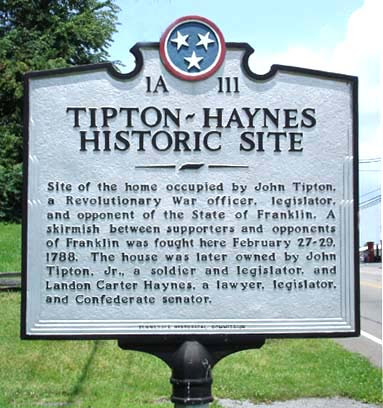

Storytelling is an art form deeply embedded in the culture of Appalachia. For centuries, families and communities have gathered around firesides, front porches, and dinner tables to share tales of the past. These stories, whether humorous, cautionary, or filled with mystery, serve as a way to pass down knowledge, values, and traditions from one generation to the next.

One of the most well-known elements of Appalachian storytelling is the “tall tale.” These larger-than-life stories often feature exaggerated characters and improbable situations, but they always carry a kernel of truth about the human experience. In many ways, these stories reflect the wit and creativity of the people who live in this challenging and often isolated region.

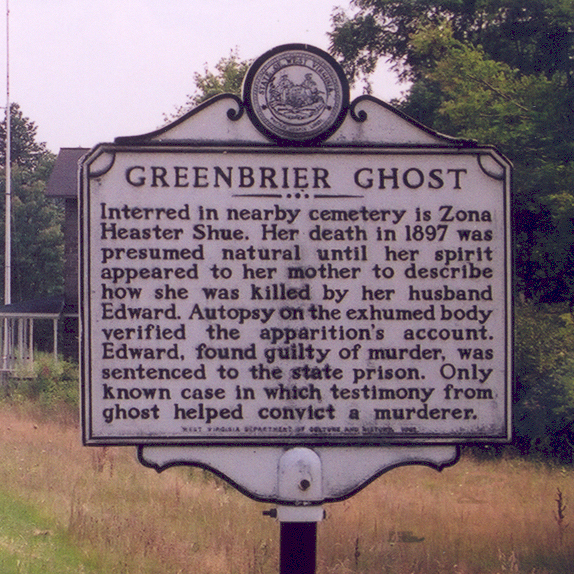

In addition to the tall tales, Appalachian storytelling also includes folk legends and myths, many of which have been passed down through the centuries. Stories of mysterious creatures like the “Wampus Cat” or the “Snipe,” as well as tales of haunted hollows, are an integral part of the region’s folklore. These stories not only entertain but also help to maintain a sense of identity, linking the present with the past.

The Spirit of Appalachia: Preserving Traditions

The music, food, crafts, and storytelling of Appalachia are more than just cultural artifacts—they are the heart and soul of the region. These practices provide a sense of continuity, connecting people across generations and allowing them to celebrate their history while looking to the future. Despite the challenges faced by the region, including economic struggles and depopulation, these traditions remain vibrant, evolving, and thriving.

In today’s world, as technology advances and cultural norms shift, it is easy for traditions to fade. However, in Appalachia, there is a strong sense of pride in preserving these practices. Local festivals, music gatherings, craft fairs, and storytelling events continue to draw people from near and far, ensuring that the region’s cultural narrative endures.

Through music, food, crafts, and storytelling, Appalachia offers a window into a world where tradition, community, and creativity are cherished above all. This rich cultural legacy remains a testament to the spirit of the Appalachian people—living, breathing, and ever evolving. I have been privileged to be raised in a beautiful part of Appalachia, and I am deeply thankful for a family that has taught me to preserve the old traditions and to tell the story of our people, who have lived in this region for many generations.

-Tim Carmichael