After eight months of writing, and researching, I’m excited to introduce my new book, The Magic of the Mountains: Appalachian Granny Witches and Their Healing Secrets. This project is deeply personal, inspired by my granny and the generations of women in my family who carried forward the traditions of healing, and storytelling.

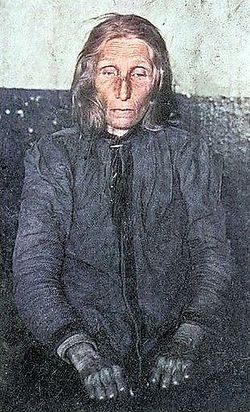

This book isn’t just about herbs, remedies, or folklore — it’s about the people who kept these practices alive. It’s about the Granny Witches, the women who knew how to soothe a fever with a handful of yarrow, ease a troubled mind with a whispered prayer, or stitch a community back together with their quiet strength. And it’s about my granny, whose hands were always busy — whether she was stirring a pot of soup, tending her garden, or teaching me the names of the plants that grew wild in the hollers.

Why This Book Matters

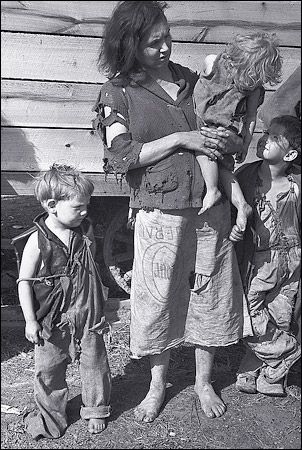

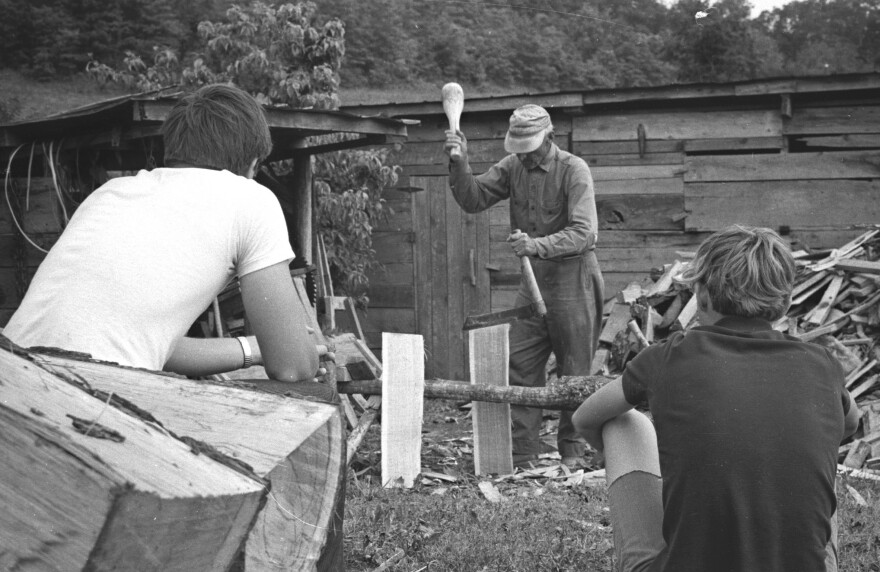

The Appalachian region is often misunderstood or reduced to stereotypes. But for those of us who grew up here, it’s a place of deep history, and resourcefulness. The Granny Witches were a vital part of that history. They weren’t magical in the fantastical sense — they were practical, and intuitive. They knew how to use what the land provided, and they passed that knowledge down through stories, hands-on teaching, and sheer necessity.

My granny was one of those women. She didn’t call herself a witch, of course — that’s a label others might use. To her, it was just life. She knew which plants could ease a stomachache, how to read the weather by the way the leaves turned, and why a cup of chamomile tea could calm a restless heart. She taught me that healing isn’t just about fixing what’s broken — it’s about understanding the rhythms of the world and working with them.

What You’ll Find in the Book

The Magic of the Mountains is a blend of storytelling, history, and practical wisdom. Here’s what you can expect:

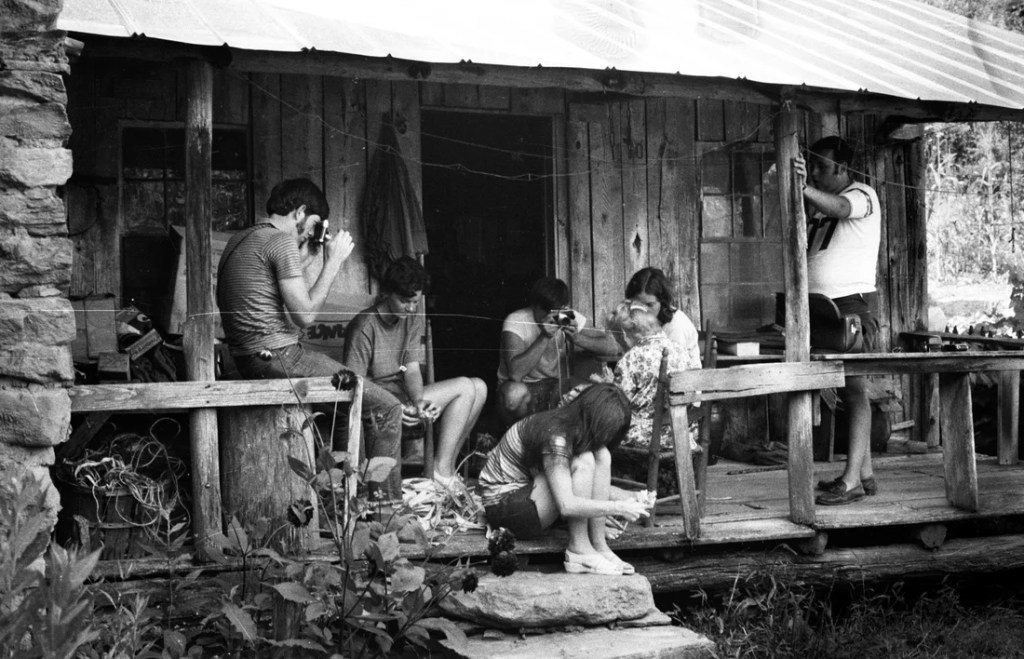

- Personal Stories: Memories of my granny and other women like her, who carried forward the traditions of Appalachian healing.

- Herbal Remedies: A guide to the plants and remedies commonly used by Granny Witches, from elderberry syrup to sassafras tea.

- Folklore and Traditions: The myths, superstitions, and beliefs that shaped the lives of these women and their communities.

- Practical Tips: How to incorporate some of these practices into your own life, whether you live in the mountains or the city.

This book is for anyone who’s ever felt drawn to the simplicity and wisdom of the past. It’s for those who want to learn about the grit of Appalachian women and the ways they cared for their families and communities. And it’s for anyone who’s ever sat at the feet of a grandmother, aunt, or elder and listened to their stories with wide-eyed wonder.

A Labor of Love

Writing this book was a journey — one that took me back to my roots and reminded me of the strength and ingenuity of the people who came before me. It wasn’t always easy. There were days when the words didn’t flow, when I questioned whether I could do justice to the stories I was trying to tell. But in the end, I kept coming back to my granny’s voice, her laughter, and her unwavering belief in the power of kindness, hard work, and a little bit of know-how.

I hope this book honors her legacy and the legacies of all the Granny Witches who came before her. And I hope it inspires you to look at the world a little differently — to see the magic in the everyday, the wisdom in the wild, and the strength in the stories we carry with us.

The Magic of the Mountains: Appalachian Granny Witches and Their Healing Secrets is available now. I can’t wait for you to read it and discover the magic for yourself.

-Tim Carmichael