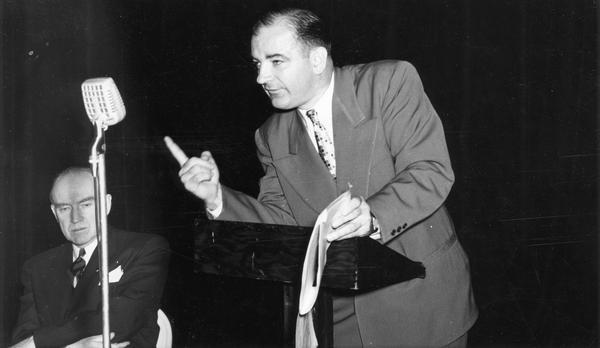

On February 9, 1950, in the Appalachian city of Wheeling, West Virginia, Joseph McCarthy delivered a speech that changed the direction of American politics. At the time, he was a relatively unknown senator from Wisconsin, a politician with little national recognition. The venue was the McClure Hotel, where the Ohio County Women’s Republican Club had gathered for their annual Lincoln Day celebration. In front of this local audience, McCarthy claimed to hold in his hand a list of 205 individuals working in the U.S. State Department who he said were known members of the Communist Party. The exact number would shift repeatedly over time, yet the claim itself was explosive. Without offering evidence or producing the supposed list, McCarthy catapulted himself from obscurity to national prominence, triggering a period of paranoia and suspicion remembered as the Red Scare.

The Wheeling speech holds symbolic importance not only because it marks the beginning of McCarthy’s meteoric rise, but also because of its location. Wheeling was not a capital city, nor was it a major industrial hub like Pittsburgh or Chicago. It was a smaller Appalachian community, geographically distant from the centers of power. Yet the fact that McCarthy launched his campaign of fear there demonstrates how anti-communist sentiment could penetrate every corner of the United States. This was not limited to urban elites or Washington insiders. Anxiety about communism reached into towns, counties, and mining regions where the rhythms of daily life were shaped by coal, industry, and community ties. Appalachia became a stage, however briefly, for the drama of national politics, illustrating how local spaces could be used to magnify national fears.

At the time of his speech, McCarthy had little to lose. He had been given the assignment to speak in Wheeling largely because his colleagues viewed him as unremarkable, a senator with limited influence. His decision to make sweeping accusations was a gamble. Rather than addressing Republican policy priorities or offering a standard Lincoln Day address, he chose to ignite controversy. His goal was to stand out in a crowded political field and to transform himself into a household name. In this sense, the Wheeling speech was less about truth and more about spectacle. It was a performance designed to exploit fear and uncertainty during a period of Cold War anxiety.

The timing mattered. In 1950, the Cold War was intensifying. The Soviet Union had tested its first atomic bomb in 1949. China had undergone a revolution that brought the Communist Party to power. Americans were absorbing news of espionage cases such as Alger Hiss and the conviction of leaders accused of passing secrets to Moscow. Against this backdrop, McCarthy’s unverified claims sounded plausible to many. Even in Appalachian communities, where day-to-day concerns often centered on wages, mining safety, and economic survival, the language of communist infiltration resonated. The idea that the enemy might be hidden within the government itself, influencing foreign policy and threatening the nation, struck a chord.

Appalachia’s own history of labor unrest also played a role in shaping how McCarthy’s claims were received. During the early twentieth century, coal miners and industrial workers across the region had built powerful labor movements. Some organizers drew inspiration from socialist and syndicalist traditions, pushing for collective bargaining, fair wages, and improved working conditions. By the mid-century, however, these earlier associations with left-wing politics came under suspicion. In the climate of the Red Scare, even distant echoes of radical labor activity were recast as potential threats. McCarthy’s message found fertile ground among those who feared that organized labor could be linked to communist influence.

This climate of suspicion created deep divisions. Communities that had once rallied around solidarity in the mines or in industrial plants now found themselves polarized. Neighbors questioned one another’s loyalties. Political figures who sought to criticize McCarthy’s tactics risked being labeled as sympathizers. The chilling effect extended into churches, schools, and local organizations, where silence often became a safer choice than open disagreement. McCarthy’s rise demonstrated how fear could be weaponized to undermine trust in democratic institutions. His methods discredited legitimate investigations into espionage by drowning them in a sea of baseless accusations.

The unraveling of McCarthy’s power came only after he overreached. In 1954, the Army-McCarthy hearings were broadcast on national television. Viewers across the country witnessed his aggressive and bullying style. Rather than appearing as a protector of American values, he appeared reckless, vindictive, and unprincipled. Public opinion turned, and later that year the U.S. Senate voted to censure him. Although he remained in office until his death in 1957, his influence collapsed. The Wheeling speech, which had once elevated him to the heights of political power, came to symbolize the dangers of demagoguery.

For Wheeling and for West Virginia, McCarthy’s appearance left a lasting mark. The city became permanently tied to the story of the Red Scare. Even though McCarthy’s career ended in disgrace, his choice to use Wheeling as the launching pad for his campaign shows how local communities can become unwitting participants in national hysteria. The McClure Hotel remains a landmark, remembered less for its hospitality than for its role in ushering in a dark chapter of American politics. Appalachia, often portrayed as isolated or disconnected, was drawn directly into the orbit of Cold War politics.

The echoes of McCarthy’s tactics reverberate into the present. Today, the United States faces new waves of political polarization, with movements that thrive on populist rhetoric and appeals to fear. The MAGA movement, led by Donald Trump and his allies, shares striking similarities with McCarthyism. Both rely on framing politics as a battle between patriotic citizens and hidden enemies. Both capitalize on national anxieties, whether those concerns involve communism during the Cold War or immigration, cultural change, and perceived threats to national identity in the present day. Both employ accusations that often lack evidence, yet gain traction through repetition and spectacle.

Much like McCarthy’s Wheeling speech, Trump’s rallies function as performances. They are designed not primarily to inform, but to galvanize. At these events, enemies are named and vilified, whether they are political opponents, journalists, or entire institutions. The underlying message is one of suspicion: that powerful forces are secretly working against the people. The strength of this strategy lies in its ability to simplify complex issues into stark divisions of loyalty and betrayal. McCarthy spoke of communists hidden within the State Department. Trump and his supporters speak of a “deep state” working within government agencies. Both narratives create a sense that unseen forces are undermining democracy from within.

Appalachia once again provides a revealing context. Many communities across the region face economic challenges, from the decline of coal to limited job opportunities. As in the 1950s, frustration and uncertainty create conditions in which populist rhetoric can thrive. Appeals to loyalty and nationalism resonate strongly when livelihoods feel precarious and traditional industries fade. The Wheeling speech demonstrates that leaders can use moments of vulnerability to present themselves as protectors, even while offering few concrete solutions. The MAGA movement mirrors this dynamic, channeling grievances into a politics of resentment and suspicion.

Another similarity lies in the impact on national unity. McCarthyism fractured trust, turning citizens against one another. Allegations of disloyalty damaged careers, friendships, and communities. The MAGA era has produced comparable divisions. Families, congregations, and neighborhoods find themselves split along partisan lines, with disagreements that extend beyond policy into identity itself. As with McCarthyism, the atmosphere of suspicion threatens to erode democratic norms.

The lessons of Wheeling are therefore more than historical curiosities. They offer a cautionary tale. McCarthy’s rise showed how quickly fear can be manipulated to generate power, and how difficult it can be to counter falsehoods once they gain traction. His fall showed that demagoguery eventually consumes itself, especially when exposed under the scrutiny of an engaged public. Yet the damage he inflicted on trust and discourse endured long after his censure.

In our present moment, it is worth remembering that McCarthy’s power began with a single speech delivered in a small Appalachian city. From that modest stage, a national hysteria spread. Today’s political climate reveals the same potential for local events and populist messages to influence the entire nation. When fear is used as a tool, and when political ambition outweighs truth, the consequences reach far beyond the initial audience. Wheeling reminds us that vigilance is required everywhere, from the smallest communities to the largest cities, to preserve the integrity of democratic life.

The Red Scare is often taught as a story of Washington hearings and high-level intrigue, yet its origins in Wheeling show a different dimension. It began in a ballroom filled with citizens gathered to honor Lincoln, citizens who likely did not anticipate that they were witnessing history in the making. McCarthy transformed that ordinary gathering into the spark for a national movement. Today, political movements continue to emerge from unexpected places. They reveal how local settings, when paired with ambitious leaders, can alter the national trajectory. The challenge remains to distinguish between those who lead with integrity and those who exploit fear.

McCarthy’s Wheeling speech belongs to the history of Appalachia as much as to the history of the nation. It stands as a reminder that even the most remote communities are never far from the currents of national life. The same is true in the present, where the struggles and anxieties of everyday citizens continue to shape, and to be shaped by, the politics of fear and spectacle. Appalachia’s connection to McCarthyism is therefore not an isolated episode. It is a window into how political demagogues can rise, how movements take hold, and how vigilance is required to safeguard democracy against those who seek to undermine it.

-Tim Carmichael

Leave a reply to Tim Carmichael Cancel reply