The Tennessee Voucher Program has become one of the most debated education policies in the state. When it launched, the level of interest stunned even its supporters. Families submitted more than 42,000 applications for the program. Yet the number of available seats was capped at 20,000, and all of those seats were quickly reserved. Students who received scholarships came from 86 of the state’s 95 counties, and they enrolled at 220 of the 241 eligible private schools. Supporters celebrated these figures as proof that the program filled a real need. Critics, however, saw something different. Beneath the surface, the numbers reveal an unfair burden, a heavy shortfall in funding, and an outcome that leaves poor families without a real path forward.

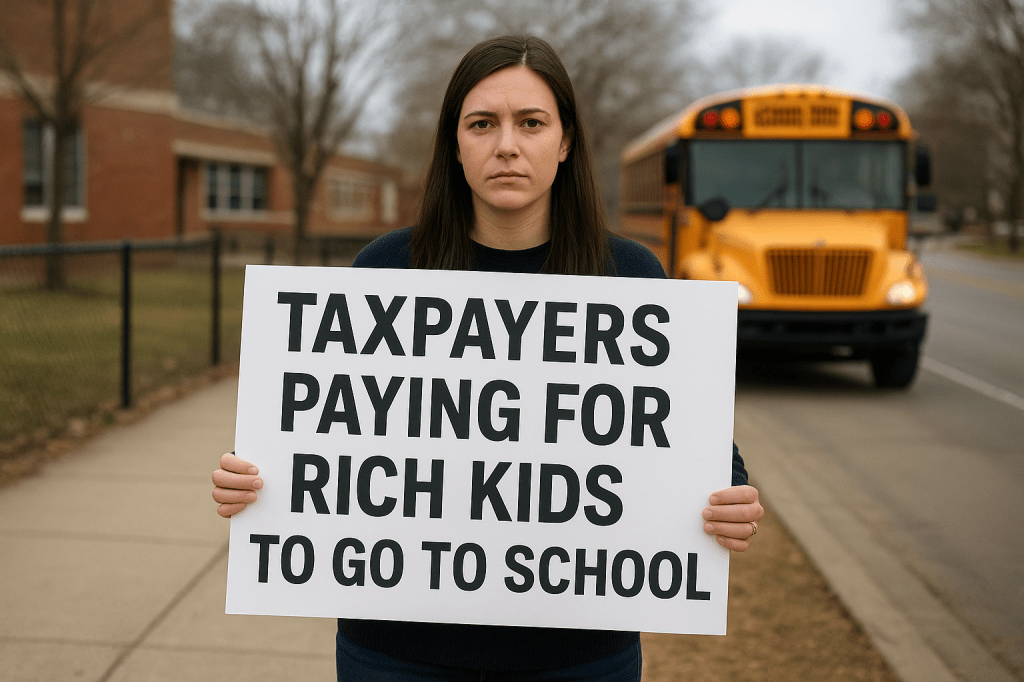

A major point of concern has been that Governor Bill Lee’s administration has chosen not to track how many of the voucher recipients were already enrolled in private schools before receiving taxpayer money. This lack of oversight raises questions about the true purpose of the program. If a significant share of voucher students were already in private schools, then the program functions less as a tool of opportunity for disadvantaged children and more as a subsidy for families who had already chosen and could already afford private education. By refusing to measure that impact, the state removes an important layer of accountability, making it difficult to know whether the program is serving its intended audience or simply rewarding wealthier households with public dollars.

The rules that guide the program divide the 20,000 vouchers into two main income groups. Half of the seats, meaning 10,000, go to families who earn more than $1 million a year. The other half go to families who earn $173,000 or less. While that split was presented as a way to create balance, many argue it is anything but balanced. Families who already have immense resources are being given taxpayer money to cover tuition they could afford without public assistance. Wealthy families benefit directly, while working families and the poor continue to face obstacles they cannot overcome.

Each voucher is set at $7,295. That may sound helpful until you consider the actual cost of private schools across Tennessee. The average annual tuition stands at about $11,886. That leaves a shortfall of roughly $4,591 per student. For families sending more than one child to private school, the out-of-pocket cost becomes enormous. Wealthy families can cover this without much difficulty. Families in the middle income range might stretch their budgets to make it work. For poor families, it is impossible. They cannot take on an extra $4,600 per year per child, and that figure does not even include additional fees.

The gap between voucher amount and true cost is not the only problem. Private schools often charge for books, uniforms, technology, extracurricular activities, transportation, and other fees that can add thousands more to the bill. None of these are covered by the voucher. For a family with limited income, those charges represent a barrier that cannot be crossed. Even if a poor family were awarded a voucher, they would face costs they could never meet. The scholarship becomes little more than a symbol, a piece of paper that offers a promise without delivering real opportunity.

Families making under $100,000 are in the hardest position. They are too often living paycheck to paycheck, covering rent or mortgage payments, groceries, healthcare, car payments, and childcare. Adding thousands of dollars in school costs is unrealistic. For them, the voucher is useless because it does not come close to closing the financial gap. It creates the illusion of access to private schools while excluding those who would need the help the most.

Supporters of the program argue that it gives parents freedom to choose the school that best fits their child. They believe that the competition between public and private schools will raise overall quality. They also claim that families who value education enough will find a way to cover the difference. Yet this view ignores economic reality. Poor families cannot pull money from thin air. They cannot skip healthcare, stop paying rent, or cut groceries in order to pay thousands of dollars in tuition. When supporters say families will “find a way,” what they truly mean is that wealthy families will find a way. Those who are poor will be left behind.

The structure of the program shows a clear preference for wealthy households. Half of the vouchers are dedicated to families who already earn more than $1 million. These families need no financial help. Taxpayers are now covering part of their private school tuition even though they could pay for it themselves. This is not about helping the needy. It is about subsidizing privilege. Poor families, meanwhile, remain stuck in schools with fewer resources, because the voucher program drains money away from the public system they rely on.

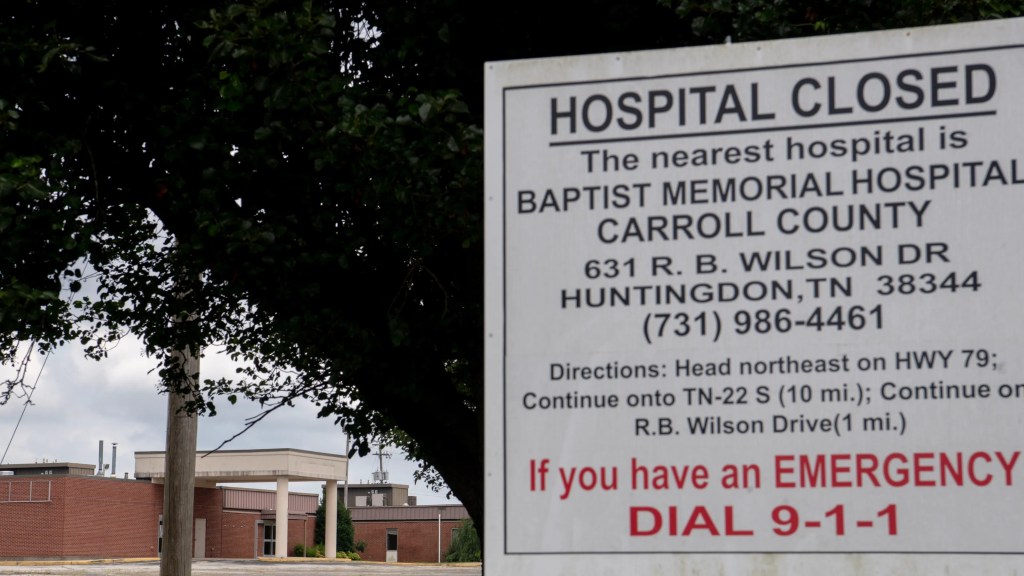

Lawmakers promoted the voucher bill as a win for Tennessee families. Yet critics see it as a deliberate shift of funds from public schools to private institutions. Public schools serve the vast majority of Tennessee’s children. Many of those schools already struggle with outdated materials, overcrowded classrooms, and teacher shortages. Redirecting millions of taxpayer dollars to private schools only deepens those struggles. Families in rural areas are even more excluded. Many rural counties have few or no private schools at all. Families there cannot use vouchers even if they receive them, yet their public schools will still lose funding.

The injustice is clear when looking at who shoulders the burden. Wealthy families receive subsidies that make their lives easier. Middle income families may stretch their budgets or take on debt to use the voucher. Poor families cannot use it at all. The families who need help the most are the ones who benefit the least. The program locks them out of private education while making them watch their tax dollars flow into institutions they will never be able to access.

Some families try to make the numbers work. They borrow from relatives, take out loans, or cut other expenses. This often results in long-term financial harm. A parent may take on debt that grows larger each year, creating pressure that affects the entire household. The stress can affect parents’ work, family stability, and even the child’s performance in school. In the end, those sacrifices often prove unsustainable. Wealthy families, meanwhile, glide through the program without such strain.

Poor families see clearly that the promise of school choice is not meant for them. It may be marketed as freedom and opportunity, yet in reality it is freedom for those who already have it and opportunity for those who least need it. The voucher amount is too small, the costs are too high, and the law that directs half of the vouchers to millionaires ensures that inequality is built into the program itself.

As the program expands, these inequities will grow. The number of vouchers is expected to rise each year. More wealthy families will receive taxpayer subsidies, and more public money will leave the schools that serve the poor. The gap between what is promised and what is possible will widen further. Families who make under $100,000 a year will remain unable to participate, no matter how many vouchers are created. For them, private school will always be out of reach.

The conversation about vouchers often includes moving stories of individual students who thrive after transferring to a private school. These stories are real and important. Yet for every student who succeeds, many more are shut out. Their families cannot pay the difference, so they stay in underfunded public schools that now have fewer resources because money has been shifted to private institutions. That is not an equal system. That is not fairness. That is a policy that favors privilege while deepening the struggles of those with the least.

Tennessee residents will need to decide what future they want. Do they want to continue paying for wealthy families to send their children to private schools? Or do they want to reform the program to make opportunity truly accessible? If the state wishes to give poor families a real chance, the voucher amount would need to cover full tuition and fees. Anything less keeps the door closed. Until that happens, poor families will continue to watch from the outside, unable to step through the doorway that the program claims to open.

The demand for better education is undeniable. More than 42,000 families applied for 20,000 vouchers. Parents clearly want alternatives. Yet demand alone does not create fairness. Without reform, the Tennessee Voucher Program will remain a system that delivers benefits to those who need them the least while excluding those who need them the most. Poor families will never be able to afford private school under this plan. They will continue paying taxes that fund scholarships they cannot use, while watching the schools their children attend lose resources year after year. This is the truth behind the celebration. Unless changes are made, the program will never be a bridge for poor families. It will remain a wall that keeps them out.

-Tim Carmichael