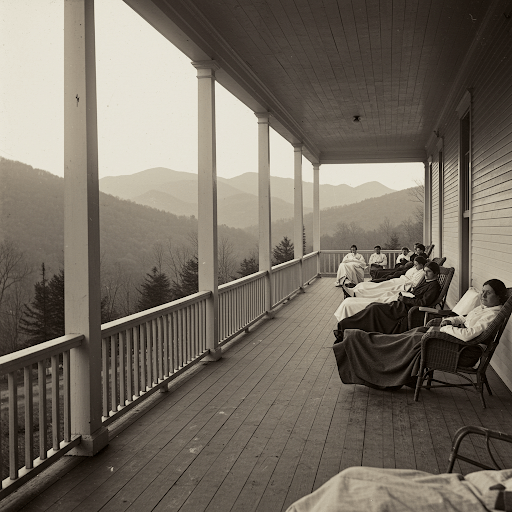

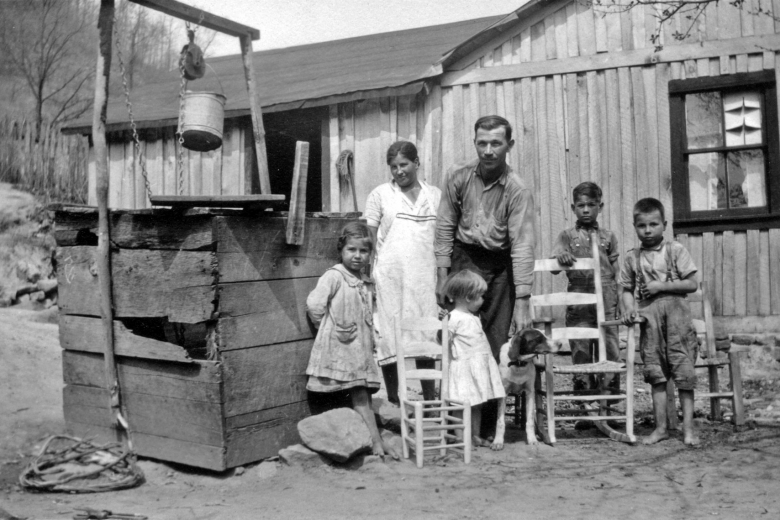

Appalachia has always had a way of doing things that’s different from anywhere else. The coal mines have been a way of life for generations, shaping the culture and identity of the people here. It’s a hard life, but it’s a life of pride. The men and women who worked those mines were known for their grit—braving dangerous conditions to provide for their families and communities. But that pride comes at a cost, one that many are still paying today, long after the mines have stopped producing.

Respiratory Problems and the Coal Mines

If you’ve lived in Appalachia long enough, you’ve seen the signs. You know someone who’s had black lung disease, or maybe it’s someone you care about who’s been struggling to breathe for years. Black lung isn’t just a thing of the past—it’s still a reality in the mountains. It’s a disease that comes from years of breathing in coal dust, and for a lot of former miners, it’s a lifelong battle.

But it’s not just black lung. Asthma and COPD are rampant here too. People in Appalachia are more likely to suffer from chronic breathing problems than anywhere else in the country. The air in mining communities is thick with dust and pollutants—left over from years of mining and from the coal-fired plants that dot the region. Even though the coal industry has shifted, the damage to the lungs of Appalachia’s people hasn’t gone away.

Cancer and the Coal Dust

Cancer rates in Appalachia are another stark reminder of the lasting effects of coal mining. Yes, smoking and diet play a role, but the environmental factors in this region are hard to ignore. Mountaintop removal mining, which has left scars across the land, releases toxic chemicals into the air and water. These toxins have been linked to cancers, especially lung cancer and cancers of the throat.

The people here have lived through decades of exposure to coal dust and other industrial pollutants, and it’s showing up in the form of higher-than-average cancer rates. For many, cancer is something they know all too well—it’s the disease that runs through their families. It’s an unfortunate byproduct of the very industry that once made their communities thrive.

The Allergy Struggle

On top of the heavy hitters like black lung and cancer, there’s a quieter issue that affects nearly everyone in Appalachia—chronic allergies. It’s not just seasonal. The constant exposure to allergens in the air, from coal dust to pollen and industrial pollutants, means many folks are popping allergy pills just to get by. You don’t have to go far in these parts to find someone who relies on antihistamines, nasal sprays, or decongestants just to breathe through the day.

In fact, studies show that nearly 30% of adults in Appalachia are on some type of allergy medication, with some areas reporting even higher numbers. The allergy season here doesn’t just last a few weeks; it’s a year-round battle. For people in mining towns, it’s often a daily struggle just to get through the day without a headache or runny nose. And it’s not just a minor inconvenience—these allergies have real effects on quality of life, making it harder to work, take care of families, or even just enjoy the outdoors.

Pride and Pain

Despite all the health challenges, there’s a deep pride in the coal mining culture. It’s a pride born from generations of hard work, sacrifice, and a sense of community. For many, mining isn’t just a job; it’s a way of life that’s been passed down, and the people who worked those mines are seen as the backbone of the region.

But pride doesn’t erase the reality of the health problems many face. The very industry that defined Appalachia has also left behind a legacy of sickness. And for those who still rely on coal for their livelihoods, the struggle continues. It’s a complicated mix of pride and pain—pride in the culture, but pain from the toll the industry has taken on the health of the people.

The question now is how to move forward. How do you honor a tradition that has shaped your community while also confronting the very real health issues it’s caused? Appalachians are known for their resilience, but no one should have to choose between their health and their heritage. It’s time for change—not just for the land, but for the people who call it home.

-Tim Carmichael