In Appalachia, history often lingers in the landscape itself, clinging to roads, hillsides, and small towns where stories outlast the people who first told them. One of the most enduring mysteries in the region centers on the Sodder children of Fayetteville, West Virginia, five siblings who vanished during a Christmas Eve house fire in 1945. What authorities described as a tragic accident became, for their family and many others, a puzzle filled with unanswered questions. Eighty years have passed, yet the fate of those children remains unresolved, suspended between official records and stubborn belief.

George and Jennie Sodder lived with their ten children in a two story frame house overlooking Route 16. George was an Italian immigrant who had built a successful trucking business and earned a reputation for speaking his mind. He openly criticized Benito Mussolini during a time when such opinions could provoke hostility, even in rural West Virginia. The family was close knit, shaped by long hours of work, shared meals, and a strong sense of loyalty. Christmas Eve in 1945 brought them together at home, with nine of the children present that night. One son was away and escaped what followed.

Sometime after midnight, the household settled into sleep. Around one in the morning, Jennie woke after hearing a loud noise on the roof, followed by a rolling sound. She searched the house and found nothing unusual, then returned to bed. Less than an hour later, she awoke again, this time to the smell of smoke. Flames had already spread through the lower level of the house, racing through the living room, dining area, kitchen, office, and the bedroom she shared with George. Panic overtook the family as smoke and heat filled the structure.

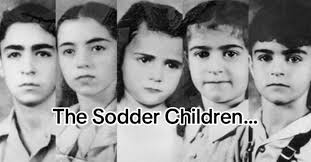

George and Jennie managed to get several children outside. Two year old Sylvia was carried from her crib to safety. Marion, age seventeen, John, age twenty three, and George Jr., age sixteen, fled from the upstairs bedroom they shared, suffering burns to their hair as they escaped. When everyone regrouped outside, five children were missing. Maurice, age fourteen, Martha, age twelve, Louis, age nine, Jennie, age eight, and Betty, age five, had been sleeping upstairs in two bedrooms at opposite ends of the hall. Between them stood a staircase already consumed by flames.

George attempted to rescue them. He smashed a window with his bare arm, tearing skin as he tried to climb back inside. Smoke and fire forced him back repeatedly. A ladder usually kept against the house could not be found. His trucks, normally parked nearby, failed to start when he tried to move them closer to reach the upper windows. Within minutes, the roof collapsed and the house fell inward, leaving nothing but burning debris. The fire burned until dawn, erasing the structure where the family had lived.

The local volunteer fire department arrived hours later, long after the blaze had consumed everything. Investigators concluded the fire was accidental, likely caused by faulty wiring. Death certificates were issued for the five missing children, listing death by fire. No bodies were recovered. Authorities claimed the blaze burned hot enough to destroy all remains, including bones. For George and Jennie, this explanation made little sense. George understood fires through his work and believed that some trace should have remained.

Doubt soon hardened into certainty. The Sodders believed their children survived. Neighbors reported seeing unusual activity that night, including lights and movement near the house during the fire. One woman claimed she saw children being carried away in a car. Another reported seeing balls of fire roll across the roof before flames erupted. A telephone repairman later stated that the Sodder phone line appeared deliberately cut. Each account added to the family’s growing belief that the fire served as a distraction.

Past encounters took on new meaning. Months before the fire, a life insurance salesman argued with George after he refused a policy. The salesman warned that George’s house would go up in smoke and his children would be destroyed. George never forgot those words. Another man who had threatened him over political disagreements later appeared on the jury that ruled the fire accidental. To the Sodders, these details suggested intent rather than coincidence.

Refusing to accept the official conclusion, the family launched its own investigation. They hired private detectives, posted reward notices, and followed leads across several states. Sightings were reported in Florida, Texas, and the Carolinas. A woman in Florida claimed she served the children breakfast the morning after the fire. Another tip suggested the siblings had been taken west and raised under different names. None of these leads produced proof, yet each sustained hope.

In the late 1940s, George ordered the fire site excavated. Investigators uncovered bone fragments that were later identified as animal remains, specifically from a cow. This discovery reinforced the Sodders’ belief that no human remains had ever been present in the debris. If the children had died in the house, George argued, something identifiable should have been found.

Perhaps the most striking symbol of the case stood for decades along Route 16. George erected a large billboard displaying photographs of the five missing children. Beneath their images were their names, ages, and a haunting question asking whether they had been kidnapped, murdered, or were still alive. For nearly forty years, travelers passing through Fayetteville saw the faces of Maurice, Martha, Louis, Jennie, and Betty staring out from the roadside. The sign turned private grief into a public demand for answers.

Time passed, though hope never fully faded. In 1967, the family received an anonymous photograph in the mail. It showed a young man in his twenties, dark haired and serious eyed, bearing a resemblance to Louis Sodder. The photo was postmarked from Kentucky and included a cryptic message on the back. The Sodders hired a detective to investigate, though the trail eventually went cold. Still, the image renewed belief that at least one child had lived beyond that night.

George died in 1969 without answers. Jennie continued the search for the rest of her life, wearing black as a sign of mourning and refusal to move on. She maintained the billboard until age and finances made it impossible. For her, believing her children lived somewhere beyond West Virginia was the only way to endure the loss.

Within Appalachia, the Sodder story became part of regional memory. Some residents accepted the official explanation, viewing the family’s suspicions as an expression of grief. Others shared the Sodders’ doubts, pointing to inconsistencies and unanswered questions. The case reflected a broader distrust of distant authority and a reliance on personal testimony that has long shaped the region’s culture.

Modern fire science has since raised further questions. Experts note that even intense residential fires rarely eliminate all skeletal remains. At the same time, no definitive evidence of kidnapping has ever surfaced. Records from the era remain incomplete, and most witnesses are long gone. Each new review of the case raises possibilities while resolving none.

It has now been eighty years since the Sodder house burned on Christmas Eve in 1945. The children remain frozen in time, forever young in faded photographs. Their faces still pose the same question that once stood beside a West Virginia highway. What happened to them remains unknown. The fire destroyed a home, reshaped a family, and ignited a mystery that continues to endure across generations. In Appalachia, the story survives as both history and haunting, refusing to fade with time.

-Tim Carmichael

Leave a comment