The world mocked the hillbilly until the hillbilly vanished. What replaced him smiled on camera, quoted Faulkner, wore vintage denim, and told stories that sold. The accent softened. The hands came clean. People called it progress. It felt more like disappearance.

Every generation in these hills carries the weight of ridicule. The word “hillbilly” once stood for stubborn pride, for people who carved homes into slopes that outsiders could not name on a map. Then it became a punchline. By the time the country started asking who the hillbilly really was, he had already been driven underground by shame and exhaustion.

I grew up hearing that word in two tones. When family used it, it sounded like affection, a way to laugh at ourselves before anyone else could. When outsiders said it, the same word came sharp, dipped in judgment. It meant ignorant, lazy, unwashed. It meant less than human. You could hear that tone in the voices on television, in jokes at the grocery store, in the classroom when kids from the city wanted to make someone feel small.

The label took root in the late nineteenth century. Reporters from northern newspapers came south hunting for curiosities after the Civil War. They found isolated communities with their own speech, music, and customs, and wrote about them as relics from an older world. “Hillbilly” appeared in print by the 1890s, a mixture of “hill” and “Billy,” the common man. It caught on fast because it gave urban readers an easy stereotype. A people turned into entertainment.

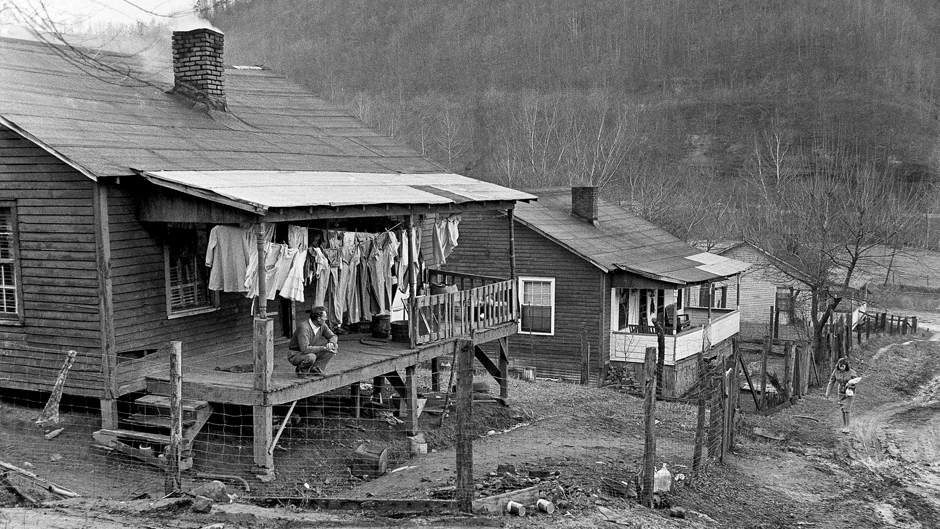

Then came the coal boom. By 1920, mines across Kentucky, West Virginia, and Tennessee drew thousands of families from nearby farms. They built towns around company stores and worked daylight to dark. The industry created wealth measured in railcars of black rock, but most of that money never stayed. Coal companies owned the land, the housing, the stores, even the schools. They kept wages in company scrip and called it opportunity. When the seams ran thin, the same companies left behind empty buildings and poisoned creeks. Appalachia kept the blame.

During those years, the hillbilly myth hardened into national culture. Hollywood and radio painted the hills as wild, funny, dangerous, or backward. The Beverly Hillbillies turned poverty into sitcom comfort. Deliverance turned fear of rural violence into art. Even later portrayals like O Brother, Where Art Thou? played with the same tension between ridicule and romance. The country learned to consume the image while ignoring the people.

By the late twentieth century, writers and musicians from the region tried to reclaim the word. They said the hillbilly represented independence and resilience. The Carter Family sang it. Loretta Lynn lived it. In their voices you could still hear the echo of people who survived isolation and hard labor with pride intact. Yet by the twenty-first century, many young Appalachians wanted distance from that history. They moved to cities for education or work and learned to smooth their voices. The word hillbilly embarrassed them. It felt like an anchor holding them to a place the rest of the country refused to see clearly.

That shame worked its way into every conversation about progress. Politicians promised to bring Appalachia into the modern age, as though the people here waited frozen in time. Development meant leaving the past behind. Even local leaders began to speak in the language of marketing, calling the region “the new frontier of opportunity.” The hillbilly no longer fit inside that narrative. He carried too much dirt on his boots.

I have watched friends build careers around Appalachian storytelling. Some grew up here, others came later and fell in love with the landscape. Their projects attract attention, funding, and praise from national outlets. They post photographs of cabins, fog over the ridges, cast-iron skillets, fiddle tunes at dusk. The imagery works because it feels safe, nostalgic, picturesque. Yet something crucial slips away in that polish. The rough humor, the quiet anger, the refusal to flatter authority. The voice that once told hard truths gets replaced by one trained to please an audience far from the mountains.

The hillbilly did not vanish in a single moment. He faded through a series of trade-offs. To earn respect, we softened our speech. To win investment, we dressed up our poverty. To keep outsiders listening, we edited our story until it fit their expectations. Each concession made sense at the time. Each one cost a little more of the raw honesty that once defined mountain life.

Some say the change brought dignity. Education expanded. Women gained more opportunities. The arts scene in places like Asheville and Berea flourished. Broadband reached towns that had waited decades for connection. Those are real victories. Yet progress also came with a quiet fear: if we speak in our old voices, will anyone take us seriously? That question lingers in classrooms and council meetings across the hills. It shapes who tells the region’s stories and how they are told.

I met a retired miner last spring in eastern Kentucky who laughed when I asked what he thought about the new Appalachian image. “They made us pretty,” he said. “We never needed pretty. We needed fair.” He remembered when the local paper printed letters in mountain dialect, when radio hosts sounded like neighbors, when pride came from work rather than presentation. “Now folks act like we should apologize for being poor,” he said. “We worked harder than any of them.”

That conversation stayed with me because it captured the contradiction at the heart of modern Appalachia. The region wants recognition, investment, and respect, yet it still fears ridicule. To solve that, many try to control the narrative. Universities host conferences on Appalachian identity. Nonprofits fund documentaries about resilience. These efforts matter, yet they often frame the people here as a cultural project rather than a living community. The hillbilly becomes a case study rather than a neighbor.

Writers like Silas House, bell hooks, and Denise Giardina have wrestled with this tension. They write about belonging without sentimentality, about faith and labor and love that endure beyond stereotype. Their work reminds readers that the region never needed outsiders to define it. Still, publishing and media industries decide which voices reach national attention. The accents that survive through editing belong to those who learned how to translate themselves.

The disappearance of the hillbilly mirrors a broader American trend. Rural identities everywhere face pressure to conform to urban norms. Authentic speech, faith, and humor shrink under professional polish. The difference is that Appalachia served as the country’s testing ground for that transformation. For more than a century, it offered a convenient otherness through which the nation measured progress. Now the region faces a choice between being understood and being genuine.

Every culture evolves, and no one should romanticize hardship or ignorance. Yet when a people erase the traits that gave them character in exchange for acceptance, something vital disappears. The hillbilly once stood for self-reliance, loyalty, and defiance. Those values built communities that survived exploitation, floods, and neglect. When we abandon that voice to please the outside world, we risk losing more than a label. We lose the rhythm of thought that shaped our endurance.

Appalachia did not kill the hillbilly out of cruelty. It happened through fatigue. After decades of ridicule, people grew tired of defending themselves. Reinvention felt like relief. The problem lies in what came afterward: a version of Appalachia that fits into marketing campaigns and tourism brochures but rarely speaks from the gut. When every story must end in uplift, truth turns quiet.

Still, the old voice surfaces when least expected. You hear it in gospel harmonies rising from small-town churches, in union meetings where retired miners debate pensions, in the laughter of women swapping stories on porch swings. It lives in the rhythm of everyday speech, in the unguarded honesty of people who never stopped calling themselves hillbillies because they never needed permission.

The future of the region may depend on how that voice evolves. Younger generations are already reshaping it through new music, writing, and film that refuse both pity and polish. They tell stories rooted in anger, humor, and grace. They understand that pride does not come from cleaning the accent off your tongue. It comes from speaking plainly, even when the world misunderstands you.

The hillbilly may have been declared dead, yet his spirit waits inside anyone who refuses to perform for approval. Appalachia has a habit of outliving its obituaries. The voice that built the region still lingers beneath the surface, ready to speak again once the applause fades. The task now is simple and hard at the same time: remember who we were before we learned to apologize.

-Tim Carmichael

Leave a comment