On December 18, 1863, in the high ridges of western North Carolina, Jane Hicks was born into a family where stories, riddles, and old songs were treasured. These were not performances in the formal sense; they were part of the fabric of life in the mountains. Her family, like many who had settled in the region, carried with them ballads that had crossed the Atlantic generations earlier. Growing up in that environment, Jane absorbed the language, rhythms, and stories that would later make her famous as one of the greatest tradition bearers of the Southern Appalachians.

She later married Jasper Newton Gentry, and together they raised nine children. Through all the labor of mountain life, Jane continued to sing. She was never far from a song, whether she was rocking a child, preparing meals, or passing an evening with neighbors. Her voice carried ancient stories, and those who heard her knew she was preserving something rare.

Jane came to be known as “a singer among singers,” and this was no idle phrase. Her gift was not simply that she knew a great many songs but that she gave them life in a way that compelled attention. Listeners spoke of her presence, her manner, and her ability to hold an audience in the spell of words and melody.

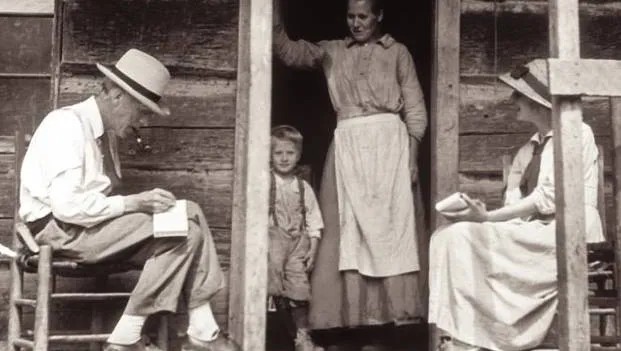

In 1916, her fame extended beyond the mountain valleys when the English folk song collector Cecil Sharp arrived in Madison County. Sharp had traveled to America in search of old British ballads that might still be alive in the Appalachian range. He had heard from Lucy Shafer, principal of the Dorland Institute in Hot Springs, that a woman named Gentry had an extraordinary repertoire. When Sharp finally met Jane, he realized the truth of Shafer’s description. From Jane alone, Sharp recorded seventy songs—more than from any other single singer he encountered. These ballads later appeared in his influential book English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, ensuring Jane’s voice reached far beyond her community.

Sharp was familiar with singers from the nearby Laurel country, but Jane’s songs were distinct. Her versions held turns of phrase and melodies shaped by her family’s traditions, demonstrating how oral culture had preserved and transformed these ballads across centuries. She did not simply repeat what had been handed down; she carried the songs with a vitality that made them her own.

Jane’s talents extended beyond ballads. She was also a storyteller, a teller of riddles, and a guardian of folk narratives. For people in her community, these forms of expression were more than entertainment. They were teaching tools, a way to pass wisdom, and a method of holding history close. Through her, the old ways continued to breathe.

Her life, though devoted to family and work, was also a life of cultural preservation. In the Gentry home in Hot Springs, songs from Britain and Ireland mingled with uniquely American stories. Children grew up surrounded by this living tradition. Jane’s descendants and relatives carried the songs further. One of her extended family members, Frank Proffitt, would later be linked to the survival of the ballad that became known as “Tom Dooley.” That tragic story, passed through generations, eventually gained international fame when the Kingston Trio recorded it in the 1960s. The fact that both Jane and Frank stand as key figures in the preservation of Appalachian music speaks to the depth of the Hicks family’s cultural legacy.

Though Jane lived her entire life in the mountain country, her songs traveled farther than she ever did. Scholars, musicians, and collectors have continued to cite her as one of the most important sources of traditional ballads in America. The versions she gave Sharp preserved both the language of Elizabethan England and the shaping influence of Appalachian life. In every stanza she sang, one can hear both the echoes of Europe and the mark of the New World.

Today, those who visit Hot Springs, North Carolina, can still see the Gentry house, standing as a testament to her life. A historical marker placed in front of it honors her memory, acknowledging the role she played in safeguarding a treasure of cultural heritage. Though the town lies only a few miles from the Laurel country, Jane’s music was unlike that of her neighbors, and this distinction continues to be remembered.

When she passed away on May 29, 1925, Jane was laid to rest in the Odd Fellows Cemetery in Hot Springs. Her grave rests among the same hills where she had lived, sung, and raised her children. It is a fitting resting place, for the mountains had always been both her home and the wellspring of her art.

The story of Jane Hicks Gentry is not only the story of a remarkable individual but also the story of Appalachia itself. In her songs, we hear the persistence of tradition in a land shaped by hardship and beauty. Her voice reminds us that culture is not preserved by books or institutions alone; it survives in families, in evenings spent around the hearth, and in the voices of those who care enough to remember.

Her legacy continues in the work of scholars, in the performances of folk singers who keep her ballads alive, and in the recognition that Appalachian culture has a richness deserving of respect. For those who hear recordings or read transcriptions of the songs she gave Sharp, there is the sense of entering a world both familiar and distant, where words hold memory and music carries history.

Jane Hicks Gentry never sought fame. Her singing grew from the life she lived and the traditions of her family. Yet through her, an entire cultural inheritance was carried forward. She is remembered as one of the greatest voices of Appalachia, a singer whose songs bridge centuries and continents, a woman whose life in the mountains gave the world a gift that continues to resonate.

-Tim Carmichael

Leave a comment