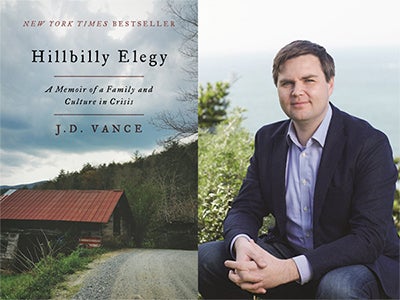

When J.D. Vance first published Hillbilly Elegy in 2016, the book was quickly embraced as a cultural touchstone, an explanation, at least in the eyes of many coastal journalists, for the rise of working class resentment in white, rural America. Billed as a memoir, it chronicles Vance’s upbringing in a struggling Rust Belt town in Ohio and his family’s Appalachian roots in eastern Kentucky. The narrative is deeply personal, but it was received and marketed as something much larger, a sweeping diagnosis of “hillbilly” culture itself.

Now, with the book surging again on the New York Times Best Seller list amid Vance’s ascendance to national political prominence, it is worth revisiting what the memoir actually says about Appalachia and what it gets profoundly wrong. Critics from within the region have long argued that Vance perpetuates harmful stereotypes, cherry picks anecdotes to prove preconceived notions, and downplays the broader structural forces shaping Appalachian life. While Vance has framed Hillbilly Elegy as a tough love critique of his community, many Appalachians see it as a caricature that advances his career at their expense.

This article takes a close look at the book’s most controversial portrayals, especially around welfare, Appalachian culture, and the broader politics of poverty, and examines why many believe Vance misrepresents the region he claims to represent.

Welfare Stereotypes and the Myth of the “Welfare Queen”

One of the most criticized aspects of Hillbilly Elegy is its treatment of welfare recipients. Vance recounts his frustration as a young man working a low wage job while watching neighbors, who received government assistance, purchase items like T bone steaks at the grocery store. He also recalls seeing people with cell phones in line to pay with food stamps, and refers to knowing “many welfare queens,” a phrase with a long, racially coded history in American politics.

On the surface, these anecdotes are presented as authentic snapshots of Vance’s world. But the way he frames them mirrors decades of conservative talking points that depict welfare recipients as lazy, manipulative, or fraudulent. Scholars of poverty studies note that these narratives, however emotionally resonant they may be for individuals like Vance, are anecdotal distortions. Research consistently shows that fraud within welfare programs is rare, and the majority of recipients use benefits for basic needs. Moreover, access to cell phones or occasional small luxuries does not negate the lived experience of poverty.

By spotlighting these stereotypes, Vance amplifies an image of Appalachians as uniquely prone to “gaming the system.” This ignores the structural reality. Welfare in the United States is often inadequate, heavily stigmatized, and increasingly difficult to access. It also erases the countless Appalachian families who rely on programs like food stamps, Medicaid, and housing assistance not to live lavishly but to survive in regions devastated by deindustrialization and economic decline.

Generalizations About Appalachian Culture

Beyond welfare, Vance makes sweeping claims about the cultural values of Appalachians. He describes young men in his community working fewer than twenty hours a week, attributing their struggles not to a lack of opportunity but to their own laziness and fatalism. He paints Appalachian culture as one of deep pessimism, contrasting it with the optimism and grit of his grandparents, whom he credits with instilling in him a sense of discipline.

Perhaps the most glaring example comes from his retelling of an encounter with someone from eastern Kentucky who asked, “What’s a Catholic?” Vance follows with the claim that “down in that part of Kentucky, everybody’s a snake handler.” This statement is not just a stereotype but a gross exaggeration. Snake handling is a fringe practice within a tiny subset of Pentecostal churches, hardly representative of Appalachian religion as a whole. By presenting it as a cultural norm, Vance reduces the rich diversity of Appalachian faith traditions including Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, and even growing Muslim communities, to a bizarre caricature.

Such passages reinforce an image of Appalachia as backward, insular, and deficient. They also overlook the resilience, creativity, and solidarity that define many Appalachian communities. From vibrant traditions of storytelling, music, and labor organizing, to long histories of mutual aid in the face of poverty, Appalachia is more than the dysfunction Vance depicts.

The Problem of Representation: Ohio vs. Appalachia

Another major criticism of Hillbilly Elegy is that Vance presents his story as emblematic of Appalachia, when in fact his upbringing was in Middletown, Ohio, a Rust Belt town shaped by industrial decline but not within the Appalachian cultural core. While Vance’s family ties trace back to eastern Kentucky, critics argue that his lived experience was suburban and Midwestern as much as Appalachian.

This matters because Vance writes as though his personal journey explains an entire region’s supposed pathology. In reality, Appalachia is vast and diverse, stretching from southern New York to northern Mississippi, encompassing cities like Pittsburgh, Asheville, and Birmingham, as well as remote rural areas. To collapse all of this complexity into a single narrative of laziness, fatalism, and cultural dysfunction is both misleading and damaging.

As Appalachian writer Elizabeth Catte argues in her book What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, Vance’s memoir resonates with outsiders precisely because it confirms their preexisting stereotypes. It is less a work of regional representation than a political parable, one man’s story of escaping poverty through grit and military service, contrasted against a “culture” that he claims traps others in dependency.

Overlooking Structural Issues: Deindustrialization and the Opioid Crisis

Perhaps the most consequential omission in Hillbilly Elegy is its treatment of systemic forces. Vance acknowledges economic decline but quickly pivots to cultural explanations, suggesting that the real problem is a lack of personal responsibility. He minimizes the role of deindustrialization, globalization, union busting, and decades of policy neglect that devastated communities like Middletown. Instead, he emphasizes individual moral failings such as violence, addiction, and laziness as the root causes of poverty.

This framework is particularly problematic in light of the opioid crisis. Appalachia has been one of the hardest hit regions in the country, not because of cultural dysfunction but because pharmaceutical companies deliberately flooded these communities with addictive painkillers while regulators looked the other way. By treating addiction as evidence of cultural weakness rather than the result of systemic exploitation, Vance shifts blame from corporations and policymakers to the very people most harmed.

In doing so, Hillbilly Elegy aligns with a broader political narrative that individualizes poverty while obscuring structural inequality. It is easier, perhaps, to tell a story of dysfunctional families than to grapple with the collapse of an economic order that once sustained entire regions. But the cost of this narrative is that it stigmatizes poor Appalachians while excusing the systems that failed them.

The Self Made Man Myth and the Invisible Safety Net

Another irony of Vance’s memoir is its embrace of the “self made man” myth. He positions his own success, Yale Law School, a career in venture capital, a U.S. Senate seat, and now Vice President as the result of personal grit, discipline, and hard work. He acknowledges his grandparents’ role in raising him but largely downplays the institutional supports that enabled his rise.

For example, Vance served in the Marine Corps, which provided him with structure, discipline, and educational benefits through the GI Bill. These forms of government support were pivotal in his trajectory, yet he rarely frames them as such. Instead, he casts welfare programs for the poor as enabling dependency while presenting his own access to state resources as a deserved reward for personal virtue. Not to mention he had a millionaire Peter Thiel funding most of his investments.

This double standard reinforces a broader cultural myth, that some forms of government assistance such as veterans’ benefits, tax breaks for homeowners, subsidies for corporations are legitimate, while others such as food stamps or Medicaid are handouts. In reality, all of these are forms of redistribution. By obscuring this, Vance perpetuates the idea that poverty stems from moral failure rather than unequal access to resources and opportunities.

A Political Treatise Disguised as Memoir

Though marketed as a personal memoir, Hillbilly Elegy functions as a political treatise. It arrived in 2016 at the exact moment when journalists and policymakers were desperate to understand the appeal of Donald Trump among white working class voters. Vance’s story, with its mix of personal struggle and conservative moralizing, offered an easily digestible explanation. Rural whites are angry and left behind, not because of structural inequality, but because of their own dysfunctional culture.

This framing has proven politically useful, not only for the book’s reception but for Vance’s own career. He leveraged Hillbilly Elegy into a platform as a commentator, investor, and now politician. But the cost has been the reinforcement of damaging stereotypes about Appalachia, presented to a national audience as objective truth.

Many Appalachians reject this portrayal, pointing instead to traditions of solidarity, labor activism, and resilience that run counter to Vance’s narrative. They argue that the region’s struggles are not the result of cultural rot but of systemic exploitation, from coal companies to pharmaceutical giants, that has left communities struggling against immense odds.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the Story of Appalachia

Hillbilly Elegy may have captivated audiences eager for an explanation of rural white America, but it did so by flattening the complexity of Appalachia into a caricature of laziness, dysfunction, and fatalism. Vance’s anecdotes about welfare recipients perpetuate harmful stereotypes. His generalizations about Appalachian culture misrepresent the region’s diversity. His memoir overlooks the structural forces such as economic collapse, opioid profiteering, and policy neglect that have shaped Appalachian life. And his embrace of the self made man myth obscures the very forms of government support that enabled his own success.

For Appalachians, the frustration is not that Vance told his own story, it is that he framed it as the story of a region, while reinforcing stereotypes that harm real communities. With the book once again in the spotlight, it is crucial to challenge these narratives and amplify the voices of Appalachians telling their own stories on their own terms. Works like Elizabeth Catte’s What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia or Silas House’s novels offer more nuanced, empathetic, and accurate portrayals of the region.

Ultimately, Appalachia is not defined by the dysfunction Vance describes. It is defined by resilience in the face of hardship, creativity in the face of neglect, and a rich cultural tapestry that resists reduction to stereotypes. The real error of Hillbilly Elegy is not that it tells one man’s story, but that it mistakes that story for the soul of an entire people.

-Tim Carmichael

Leave a comment