Long before antibiotics were discovered, people placed their hopes in nature. And in the late 1800s, there were few places more sought after than Asheville, North Carolina—a mountain town that quietly became a place where the sick came to heal, or at least to hold on a little longer.

In 1870, Dr. H. P. Gatchell published a small but striking pamphlet titled Western North Carolina—Its Agricultural Resources, Mineral Wealth, Climate, Salubrity and Scenery. He had lived long enough to know what tuberculosis looked like—how it took strong men and women and drained them slowly, how it turned lungs into something brittle. He believed the mountains had something to offer that medicine didn’t yet have: clean, temperate air and space to rest.

A year later, Dr. Gatchell put that belief into action. He opened The Villa, a quiet facility nestled in what’s now the Kenilworth neighborhood of Asheville. It was the first sanitarium in the United States devoted exclusively to tuberculosis patients. It wasn’t grand. It didn’t need to be. What mattered was that it gave people a fighting chance in an era when the disease was often a death sentence.

People began to take notice. By the 1880s, a booklet titled Asheville, Nature’s Sanitarium was circulating through towns and cities across the country. It painted Asheville as a place of escape—where Southerners fled the stagnant, mosquito-heavy summers and Northerners sought refuge from the bitter cold and damp. Asheville offered something different. It offered stillness, elevation, and time.

Tuberculosis—known then as consumption—was relentless. There were no antibiotics, no real treatment beyond rest, food, and clean air. People traveled great distances by train, wagon, or carriage, hoping Asheville would slow the march of the disease. Families scraped together funds for the trip. Some patients came alone, having said quiet goodbyes back home, unsure if they’d return.

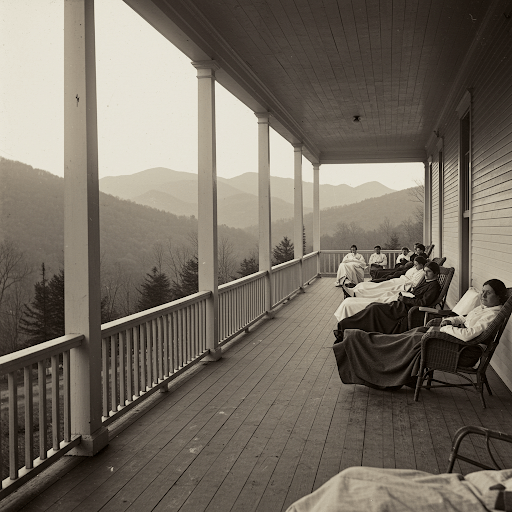

By 1900, Asheville had fully embraced its role. Porches were built wide and deep to allow patients to rest outdoors. Rooms were designed with cross-ventilation. Meals were served at regular intervals. It wasn’t a cure, but it was something to hold onto.

By 1930, the city was home to 25 sanitariums with nearly 900 patient beds. Some were small and family-run. Others, like St. Joseph’s and Highland Hospital, grew into large institutions. Each one carried stories—of slow recoveries, of losses softened by mountain views, of letters written home from wicker chairs.

And Asheville itself was changing. The influx of patients brought doctors, nurses, caretakers, and workers. It brought builders and cooks, cleaners and train conductors. The town’s growth was tied to its reputation as a place where the air could heal—or at least ease the pain.

For many, Asheville became a final chapter. But for others, it gave time—weeks, months, even years they might not have had elsewhere. Children visited their parents through screened windows. Husbands waited on benches while nurses turned mattresses. Life continued, carefully and slowly.

When antibiotics like streptomycin finally arrived in the 1940s, the need for these mountain sanitariums began to fade. The buildings were repurposed or torn down. But the legacy lingered.

Asheville wasn’t just a retreat. It was a place of second chances, even if only for a little while. Before there was medicine, there was the mountain air. And it mattered.

-Tim Carmichael

Leave a comment