I still feel it when the first warm days hit in February—that familiar pull to check the soil, to start thinking about turning ground. That’s how it was with tobacco. The calendar on our kitchen wall might have said winter, but Daddy’s mind was already on spring planting.

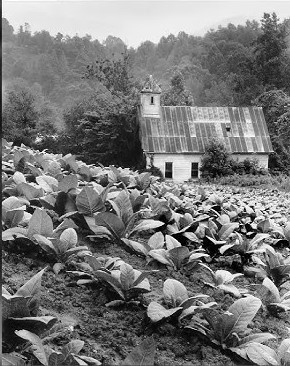

This was one of our tobacco fields

“Feel that?” Daddy would say, holding a handful of dirt as February’s cold began to break. “It’s nearly time.” I was too young to know what he felt in that soil, but I trusted him. In our part of Appalachia, tobacco wasn’t just a crop—it paid for everything from my school clothes to the lights staying on.

Daddy started seeds in old wooden frames covered with plastic sheeting. He’d mix the soil just right, adding fertilizer he’d bought last fall when prices dropped. “Too much and you’ll burn ’em up, too little and they won’t have strength,” he’d tell us boys as we helped him fill the trays.

Those seeds were tiny—almost like dust. I remember Daddy’s rough, cracked hands somehow becoming gentle as he scattered them across the soil. He’d water them with a fine mist, careful not to wash the seeds away or drown them. Then we’d wait.

While the seeds sprouted, Daddy would be out with Old Dan, our plow horse. We didn’t have money for a tractor like some farmers. Every morning, Daddy would lead that big brown horse from the barn, talking to him low and easy. “Come on, Dan. Got work to do.” Old Dan knew the routine, patiently standing as Daddy hitched the plow.

I can still see them moving across our fields—Daddy behind the plow handles, his shoulders straining, calling commands to Old Dan who pulled steady and strong. “Gee” to turn right, “Haw” to turn left. The work was slow and hard. What took other farmers a day with a tractor took Daddy three with Old Dan, but that horse was as much a part of our family as anyone.

Sometimes Daddy would let me walk alongside, teaching me how to guide the horse. “Don’t yank on him. Dan knows what he’s doing better than you do,” he’d say. By day’s end, both Daddy and Old Dan would be covered in sweat, and the smell of freshly turned earth and horse filled the air. Those evenings, I’d help Daddy rub down Old Dan, feeding him extra oats for the hard work.

By April, those dust-like seeds had become three-inch plants with bright green leaves. That’s when the real work started. With no mechanical transplanter, we set tobacco by hand. Daddy would use Old Dan to drag a special tool that made shallow furrows in the field. Then we’d follow behind—me, my brothers, and Mama—each carrying a bucket of water and an apron full of plants.

I’d make a hole with my finger, set in a plant, pour a little water, and press the soil firm around it. Plant after plant, row after row, our backs bent under the spring sun. “Keep ’em straight,” Daddy would call. “And mind your spacing.” Each plant needed room to grow big leaves, and Daddy could spot an uneven row from clear across the field.

We’d plant for days, often working until it was too dark to see. I’d fall into bed those nights, my fingers still feeling the motion of digging small holes in the dirt. Daddy would be up checking weather reports on our old radio, worried about a late frost that could kill everything we’d done.

When frost threatened, we’d all scramble out of bed before dawn. “Everybody up!” Daddy would shout. We’d hurry to the fields with sheets of plastic to cover the young plants, weighing down the edges with dirt to trap the warmth inside. Those mornings, I’d see my breath in the air while my fingers went numb with cold. One bad frost could wipe out weeks of work.

When we weren’t in school, Daddy put us to work hoeing weeds. He’d give each of us a row and expect it clean by dinner. “Weeds steal water and food from our backker,” he’d say. “Every one you miss is money out of our pockets.” On hot spring days, the sweat would roll down my back before I’d finished half a row. My brothers and I would compete to see who could work fastest, knowing Daddy was watching, judging our work with a farmer’s critical eye.

Spring rains brought relief and worry. We needed the water, but too much could drown the plants or wash them out of the ground. Daddy would pace the porch during heavy storms, his face tight with worry. A single bad storm could wipe out months of work in minutes.

By late spring, the plants would be knee-high, their leaves spreading wide. That’s when we started “topping” and “suckering”—breaking off the flower buds at the top and removing the small shoots that sprouted from the stalk. This made the plant put its energy into growing bigger leaves instead of making seeds.

It was sticky, nasty work. The plant sap would coat our hands with a black goo that no amount of soap seemed to remove. We’d go to school with stained hands that smelled of green tobacco, a smell that marked farming kids from town kids.

Spring in the tobacco fields taught me things no classroom ever could. I learned to read weather from the sky and how animals behaved. I learned that work doesn’t wait for you to feel like doing it. I learned that a family pulling together can make it through just about anything.

Daddy never made much from tobacco—a few thousand dollars in a good year, barely enough to cover what we needed. But those spring days in the fields, working alongside him and Old Dan, showed me how he faced life—head-on, no complaining, just getting done what needed doing.

Sometimes now, nearly 50 years later, when I smell freshly turned soil or hear the steady rhythm of hoofbeats, I’m right back there—a skinny kid with dirty hands, learning how to work tobacco, learning how to live from a daddy who’s no longer with us but whose lessons remain as firmly planted as those tobacco rows we once tended together.

-Tim Carmichael

Leave a comment